Making it in the music business is hard enough. The odds of meeting the right people who can get your music where it needs to be heard are not very promising. But when a Canadian musician chooses to perform a large chunk of their material French in provinces outside of Quebec, those odds get even worse. Cultural preservation is apparently more important to those artists as much as album sales. Yet ironically, something else is also important to these artists, without which their careers might never survive -- Quebec.

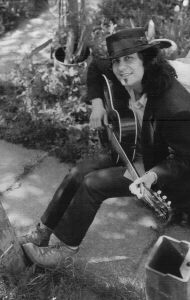

CHALLENGES "If there is a challenge, it is to maintain our language," says Danny Boudreau, a thirty-one

year old singer/songwriter who has been shaking up New Brunswick since the age of

seven with his rousing Acadian numbers and soft ballads. "Itís also a challenge not to be

tempted to go and sing in English just because the market is bigger. For me, itís natural to

sing in French because I am French myself. But I live in a region where there are English

speaker as well, and I could have chosen to sing in English."

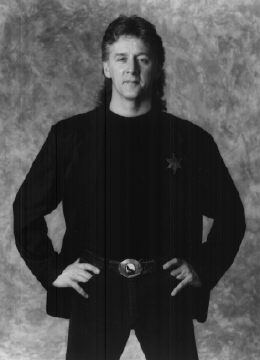

"Getting known; carving my name into the history of Franco-Ontarian performers.

Distribution is a big problem," says Jean-Guy "Chuck" Labelle, a country music recording

artist with three French CDs. "I tour a lot; thatís how Iíve been able to sell albums and

keep myself and my musicians working. I do a lot of schools in Ontario -- Iíve become

somewhat of a kidís star without doing childrenís music."

For Marcel Soulodre, the challenges of performing in French have changed over time.

Based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Soulodre was born to a French-speaking father and an

English-speaking mother and was raised as an Anglophone. So, when he made the

decision to become a professional musician, it seemed only natural to write and sing in

English. That all changed a few years ago when Soulodre re-discovered his French roots,

became bilingual, and started writing songs in French. "It was a challenge to me to reclaim

that part of me that was there, but was dormant," he explains.

Jíavais dans les yeux is his first French release, and the country/rock songs resound with

Soulodreís ease in the language. But it wasnít always like that. "I set my standards very

high. I had to re-familiarize myself with the basic rules and regulations of the language. I

wanted to express myself in French utilizing the same sort of images and metaphors I

would normally use, but learning how to utilize them in French," he says.

Now that he has mastered the language, the challenge for Soulodre is two-fold. On the

one hand he laughs that itís "finding and audience," but when he finally does have ears

eager to hear his music, itís "getting off the stage because I have so many songs that I

want to play!"

FINDING AN AUDIENCE

"If there is a challenge, it is to maintain our language," says Danny Boudreau, a thirty-one

year old singer/songwriter who has been shaking up New Brunswick since the age of

seven with his rousing Acadian numbers and soft ballads. "Itís also a challenge not to be

tempted to go and sing in English just because the market is bigger. For me, itís natural to

sing in French because I am French myself. But I live in a region where there are English

speaker as well, and I could have chosen to sing in English."

"Getting known; carving my name into the history of Franco-Ontarian performers.

Distribution is a big problem," says Jean-Guy "Chuck" Labelle, a country music recording

artist with three French CDs. "I tour a lot; thatís how Iíve been able to sell albums and

keep myself and my musicians working. I do a lot of schools in Ontario -- Iíve become

somewhat of a kidís star without doing childrenís music."

For Marcel Soulodre, the challenges of performing in French have changed over time.

Based in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Soulodre was born to a French-speaking father and an

English-speaking mother and was raised as an Anglophone. So, when he made the

decision to become a professional musician, it seemed only natural to write and sing in

English. That all changed a few years ago when Soulodre re-discovered his French roots,

became bilingual, and started writing songs in French. "It was a challenge to me to reclaim

that part of me that was there, but was dormant," he explains.

Jíavais dans les yeux is his first French release, and the country/rock songs resound with

Soulodreís ease in the language. But it wasnít always like that. "I set my standards very

high. I had to re-familiarize myself with the basic rules and regulations of the language. I

wanted to express myself in French utilizing the same sort of images and metaphors I

would normally use, but learning how to utilize them in French," he says.

Now that he has mastered the language, the challenge for Soulodre is two-fold. On the

one hand he laughs that itís "finding and audience," but when he finally does have ears

eager to hear his music, itís "getting off the stage because I have so many songs that I

want to play!"

FINDING AN AUDIENCE

"Finding an audience," as Soulodre said, is a major challenge for those living outside

centers where French is spoken by any significant amount of the population. If a

performer sings in French, they wonít get played on the radio and theyíll have a harder

time getting gigs. But to those who take this route, the rewards of bridging gaps between

cultures and languages more than make up for the lack of exposure.

"Friends of mine who are in the business tell me I should switch to English because I

would get more gigs," says Crystal Plamondon, who hails from Plamondon, Alberta (her

grandfather founded the town) and includes three languages -- French, English, and Cree

-- in her repertoire of Cajun and Zydeco influenced pop and country. "But you know

what? Iíve had the most gigs, the most paying and fulfilling gigs, because I sing in French.

Why did I get a slot on the Canada Day celebrations in Vancouver? Because Iím a

bilingual performer. There are tons of Anglophone performers. People also say to me

that they think I must have such a hard time in Alberta because of the red necks, but that is

so wrong -- people love it."

The bilingual situation is much different in New Brunswick than in Alberta. There, a large

portion of the population is French-speaking, and that makes Boudreauís job much easier.

"In my region in the north of the province, it is actually better to sing in French because

there are more places to perform and the number of French people here is very big," he

says.

When he does perform for Anglophone audiences, who often include French immersion

schools in the southern part of the province, Boudreau says the reaction is "pretty good.

Music is universal. Youíve got to give the audience something they can tap their feet to, a

melody to enjoy. The hardest thing is when I talk between songs, I have to talk very

slowly. But most of the time they were my better audience."

Soulodre agrees about the universal aspects of music. "The music cuts through most of it,

I find. Whether people listen to lyrics or not, most people get the music and thatís usually

what attracts them," he says. Therefore, the Anglophones who come to his shows "are

usually fairly appreciative. The majority of people are usually very receptive to it because

itís an opportunity for them to hear something in a different language, and a lot of them

get to learn along with me."

"Finding an audience," as Soulodre said, is a major challenge for those living outside

centers where French is spoken by any significant amount of the population. If a

performer sings in French, they wonít get played on the radio and theyíll have a harder

time getting gigs. But to those who take this route, the rewards of bridging gaps between

cultures and languages more than make up for the lack of exposure.

"Friends of mine who are in the business tell me I should switch to English because I

would get more gigs," says Crystal Plamondon, who hails from Plamondon, Alberta (her

grandfather founded the town) and includes three languages -- French, English, and Cree

-- in her repertoire of Cajun and Zydeco influenced pop and country. "But you know

what? Iíve had the most gigs, the most paying and fulfilling gigs, because I sing in French.

Why did I get a slot on the Canada Day celebrations in Vancouver? Because Iím a

bilingual performer. There are tons of Anglophone performers. People also say to me

that they think I must have such a hard time in Alberta because of the red necks, but that is

so wrong -- people love it."

The bilingual situation is much different in New Brunswick than in Alberta. There, a large

portion of the population is French-speaking, and that makes Boudreauís job much easier.

"In my region in the north of the province, it is actually better to sing in French because

there are more places to perform and the number of French people here is very big," he

says.

When he does perform for Anglophone audiences, who often include French immersion

schools in the southern part of the province, Boudreau says the reaction is "pretty good.

Music is universal. Youíve got to give the audience something they can tap their feet to, a

melody to enjoy. The hardest thing is when I talk between songs, I have to talk very

slowly. But most of the time they were my better audience."

Soulodre agrees about the universal aspects of music. "The music cuts through most of it,

I find. Whether people listen to lyrics or not, most people get the music and thatís usually

what attracts them," he says. Therefore, the Anglophones who come to his shows "are

usually fairly appreciative. The majority of people are usually very receptive to it because

itís an opportunity for them to hear something in a different language, and a lot of them

get to learn along with me."

Ironically, the only place where Plamondon has a problem is in Quebec. "When they book

me they will tell me they donít want any English. When I get to the show Iíll put in the

Daniel Lanois song ĎUnder A Stormy Sky,í which is like maybe five percent English, and

after the show Iíll say ĎSo, did you have a problem with my English songs?í And theyíll

say, ĎOh, I didnít even know you sang any.í" she laughs.

The music moguls in Quebec also donít have a problem with Plamondonís Cree selections.

"Quebec is really mainstream in a sense they are almost like FM radio. They listen to the

Celtic, theyíll love the Cree, but they wonít like the English. Itís like the people in the rest

of Canada. Theyíll listen to Celtic and theyíll listen to Kashtin [a Native duo that

performs in the Innu language] but they donít want to hear French on English radio."

Labelle knows about the fickle nature of radio all too well. Four years ago he was

commissioned to write the song "Look At Me, Iím Climbing" for the Special Olympics.

As requested of him, the song contained both French and English lyrics. "The French

radio stations would not play it because it had English content, and the English radio

stations would not play it because it had French content. So, boy, did I learn a lesson

there!" he says. The song went nowhere as a result of scant airplay, and when approached

to write another song for the national Special Olympics in 1998, Labelle did not go the

bilingual route.

QUEBEC: FRIEND OR FOE?

Although Quebec might seem to be a haven for those who sing in French, since for many

years the province has supported its own music industry, in recent times the market has

become saturated, the gigs fewer, and the same names cropping up over and over again,

with others disappearing into nowhere. As Soulodre explains, "itís a very difficult market

to get into as an artist because youíre regarded as an outsider. They are having enough

trouble propping up their own industry these days because itís saturated and might be

falling in on itself a little bit, with Ďhere today gone tomorrowí kinds of artists."

"I did a television show in Montreal last year for a few months," says Plamondon. She

hosted the first and only French country music show in Canada on MusiMax, the sister

station to Musique Plus. "That was a godsend for me because I saw that thereís no work

for performers out there. They have Montreal as their main center but they canít work all

the time. They only work in the summer months because of all the festivals then."

"Thereís so many artists coming out of Quebec that you really need to give them

something that theyíll flip over. They wonít take any chances. If itís good theyíll take it,

but if youíre from Quebec I would say your chances are a lot better than if you are from

outside," says Boudreau, who is getting ready to record the follow-up to his 1994 release

Sans Detour.

Ironically, the only place where Plamondon has a problem is in Quebec. "When they book

me they will tell me they donít want any English. When I get to the show Iíll put in the

Daniel Lanois song ĎUnder A Stormy Sky,í which is like maybe five percent English, and

after the show Iíll say ĎSo, did you have a problem with my English songs?í And theyíll

say, ĎOh, I didnít even know you sang any.í" she laughs.

The music moguls in Quebec also donít have a problem with Plamondonís Cree selections.

"Quebec is really mainstream in a sense they are almost like FM radio. They listen to the

Celtic, theyíll love the Cree, but they wonít like the English. Itís like the people in the rest

of Canada. Theyíll listen to Celtic and theyíll listen to Kashtin [a Native duo that

performs in the Innu language] but they donít want to hear French on English radio."

Labelle knows about the fickle nature of radio all too well. Four years ago he was

commissioned to write the song "Look At Me, Iím Climbing" for the Special Olympics.

As requested of him, the song contained both French and English lyrics. "The French

radio stations would not play it because it had English content, and the English radio

stations would not play it because it had French content. So, boy, did I learn a lesson

there!" he says. The song went nowhere as a result of scant airplay, and when approached

to write another song for the national Special Olympics in 1998, Labelle did not go the

bilingual route.

QUEBEC: FRIEND OR FOE?

Although Quebec might seem to be a haven for those who sing in French, since for many

years the province has supported its own music industry, in recent times the market has

become saturated, the gigs fewer, and the same names cropping up over and over again,

with others disappearing into nowhere. As Soulodre explains, "itís a very difficult market

to get into as an artist because youíre regarded as an outsider. They are having enough

trouble propping up their own industry these days because itís saturated and might be

falling in on itself a little bit, with Ďhere today gone tomorrowí kinds of artists."

"I did a television show in Montreal last year for a few months," says Plamondon. She

hosted the first and only French country music show in Canada on MusiMax, the sister

station to Musique Plus. "That was a godsend for me because I saw that thereís no work

for performers out there. They have Montreal as their main center but they canít work all

the time. They only work in the summer months because of all the festivals then."

"Thereís so many artists coming out of Quebec that you really need to give them

something that theyíll flip over. They wonít take any chances. If itís good theyíll take it,

but if youíre from Quebec I would say your chances are a lot better than if you are from

outside," says Boudreau, who is getting ready to record the follow-up to his 1994 release

Sans Detour.

Labelle agrees. "They want to keep the business home. It would require so much energy

from my team to push me into there. I would probably have to move to Montreal," which

he explains would cause his emerging English career (he is currently working on No

Getting Over You, his first all-English release) to falter. "Hereís the Catch-22 : ĎHeís

singing in French but heís really English.í I donít want to get into that. Iím just a singer,

you know, Iím a songwriter -- who happens to be bilingual."

Despite its saturated music scene and the apprehension of outsiders, Quebec is still very

much important to these performers. When asked what would happen to them without

Quebec, Plamondon asks wryly, "You mean what would happen if they separated?"

"The province is important to us in the sense that anything Francophone in Canada --

cultural grants and schools, for example -- comes from Ottawa and Montreal or Quebec

City. So in that sense it would be harder for us," she explains. "Something very funny is

that once people know I am Franco-Albertan, they have no problem with the French.

They all ask me ĎAre you Quebecois?!?í and I say no, and explain my background to them.

What they are tired of is that Quebec wants special treatment. They donít want o hear

French shoved at them if it comes from Quebec. And I donít either -- Iím just as angry

about it as they are. Iím not Quebecois. Thereís 172 000 Francophones here, and most

of them were born here."

"For some people [Quebec is] very important depending on what you want to do," says

Soulodre. "My ambitions lie in Europe. Thatís always been the case since I started in

French and checked out the Montreal scene and realized what it was like. A lot of the

people in the Quebec industry laugh at me for wanting to do that. They say, ĎOh, itís so

difficultí."

"The industry here in New Brunswick is very new," says Boudreau. "There has always

been music, but there were no studios, or managers -- no infrastructure to allow us to

produce good albums. Since 1994 all that has changed quite drastically. Then a program

was established to inject a lot of money into studios. There were about 30 albums

produced in French in 1994 which was more than the past 25 years. But if we want to

survive in what we are doing, just the New Brunswick market isnít enough."

The goals of these artists are very much along the lines of what Boudreau describes as "to

play in front of more people and to be able to live off of our music, of our art. My main

goal has always been just to keep on enjoying what I am doing and have people enjoy

what I am doing."

Labelle agrees. "They want to keep the business home. It would require so much energy

from my team to push me into there. I would probably have to move to Montreal," which

he explains would cause his emerging English career (he is currently working on No

Getting Over You, his first all-English release) to falter. "Hereís the Catch-22 : ĎHeís

singing in French but heís really English.í I donít want to get into that. Iím just a singer,

you know, Iím a songwriter -- who happens to be bilingual."

Despite its saturated music scene and the apprehension of outsiders, Quebec is still very

much important to these performers. When asked what would happen to them without

Quebec, Plamondon asks wryly, "You mean what would happen if they separated?"

"The province is important to us in the sense that anything Francophone in Canada --

cultural grants and schools, for example -- comes from Ottawa and Montreal or Quebec

City. So in that sense it would be harder for us," she explains. "Something very funny is

that once people know I am Franco-Albertan, they have no problem with the French.

They all ask me ĎAre you Quebecois?!?í and I say no, and explain my background to them.

What they are tired of is that Quebec wants special treatment. They donít want o hear

French shoved at them if it comes from Quebec. And I donít either -- Iím just as angry

about it as they are. Iím not Quebecois. Thereís 172 000 Francophones here, and most

of them were born here."

"For some people [Quebec is] very important depending on what you want to do," says

Soulodre. "My ambitions lie in Europe. Thatís always been the case since I started in

French and checked out the Montreal scene and realized what it was like. A lot of the

people in the Quebec industry laugh at me for wanting to do that. They say, ĎOh, itís so

difficultí."

"The industry here in New Brunswick is very new," says Boudreau. "There has always

been music, but there were no studios, or managers -- no infrastructure to allow us to

produce good albums. Since 1994 all that has changed quite drastically. Then a program

was established to inject a lot of money into studios. There were about 30 albums

produced in French in 1994 which was more than the past 25 years. But if we want to

survive in what we are doing, just the New Brunswick market isnít enough."

The goals of these artists are very much along the lines of what Boudreau describes as "to

play in front of more people and to be able to live off of our music, of our art. My main

goal has always been just to keep on enjoying what I am doing and have people enjoy

what I am doing."